Art in the time of war

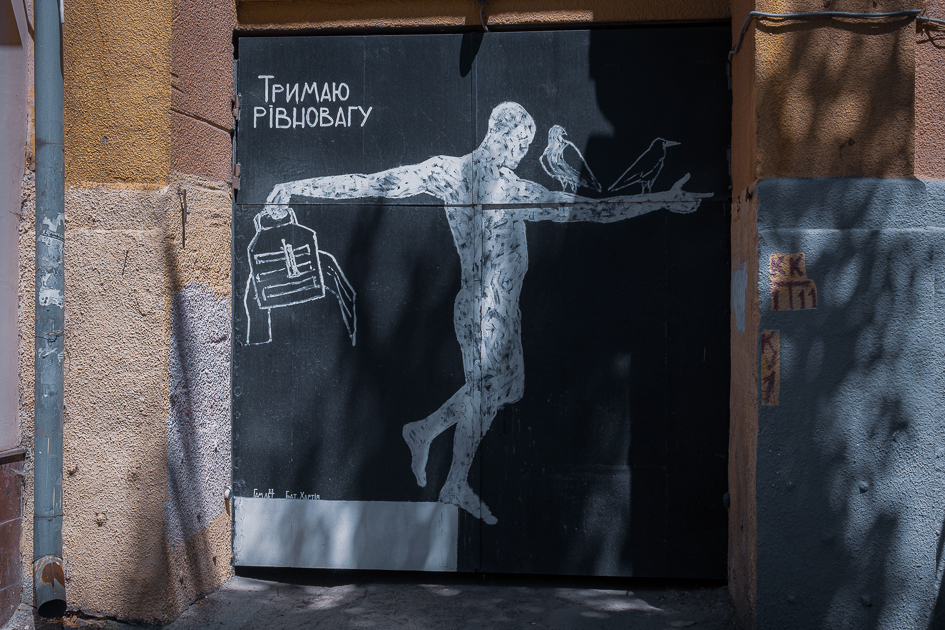

Kharkiv lies just 25 kilometers from the front, but its cultural life adapted to the harsh reality of war, and even found new ways to flourish.

In the past two and a half years, the city has been going through the hard process of conditioning to the demands, sacrifices and risks of wartime. It was under siege, with long periods of regular blackouts and heartbreaking human losses among the scarred cityscape. Today it keeps on living under constant threat, with a big part of its population evacuated without no return in sight.

But compared to many other big cities close to the frontline – Sumy, Chernihiv, Zaporizhzhia or Dnipro – Kharkiv is successful in preserving and reconstituting its status of the vibrant hub of art and culture, with a shared aim of supporting the mental resolve of the citizens and soldiers – all despite the fact that Russian missiles and drones can reach its borders in minutes.

Officially, the government-issued ban on big public events is in place; every cultural building can be a prime target for a Russian terror attack. So both the high and the popular art and culture went on underground, with venues organized for secretive performances, invitations spread secretly by word of mouth among the trusted.

Some artists left in Kharkiv can not imagine the life outside of it, occasionally despite having a family abroad and an option to work in the West. But their creative hearts are tied to the city they live in. The members of Kharkiv’s art community are united by the circumstances they found themselves in, and their resolve is to continue on, together serving the community by creating a cultural refuge for the citizens, raising the money to support their fellows in the military, and building a worthy wartime legacy to come back to some day.