The Art of Little Syria

Druze’s precarious position in the new reality

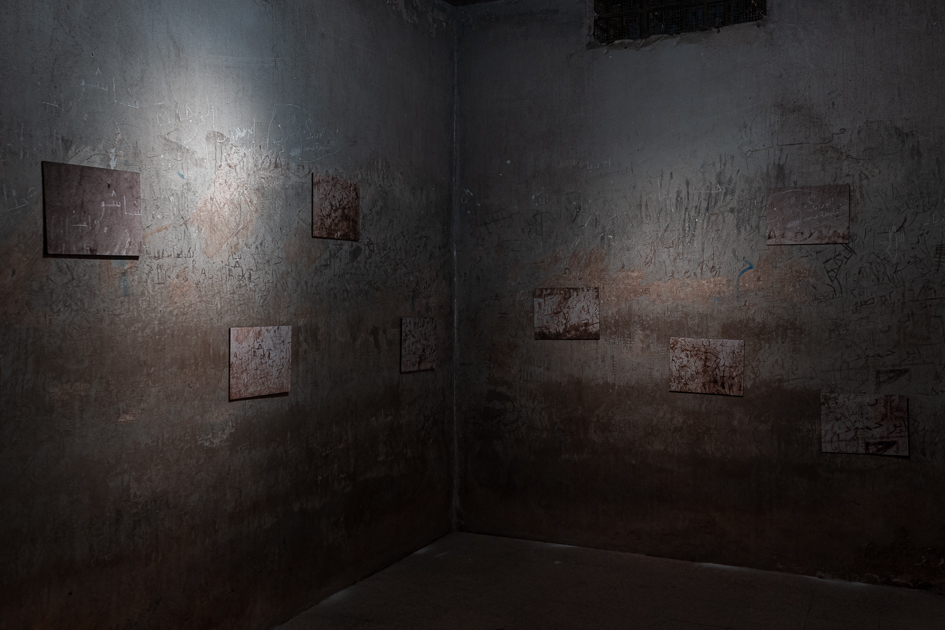

Khalid Barake, an influential Druze contemporary artist, returned to Syria after fourteen years of exile to fill the cultural void following the fall of the Assad regime. In the heart of the Damascus district of Jaramana, in a building that was once a symbol of repression, Khalid has created a space of freedom. The former police station, for years the site of the regime’s detentions and brutal interrogations, became home to an interdisciplinary exhibition exploring addiction and the fate of people convicted of drugs, created by a collective set up by Khalid. The artists transformed the site into a centre for dialogue about addiction, justice and Syria’s past. Among the bustling streets of Jaramana, dubbed ‘Little Syria’ by its religious and ethnic diversity, local artists are creating a new narrative. The opening of the exhibition was meant to be a manifesto of unity, a demonstration that art and culture are beyond divisions, but the political crisis has revised these aspirations.

In the beginning of May, a wave of armed riots swept through Jaramana, costing a total of a dozen people their lives. The sectarian clashes took place in several Druze-populated villages in the south of the country, echoing tensions between the more radical Sunnis and Druze that erupted after a fake video was released on the internet in which a Druze spiritual leader insults the Prophet Muhammad. A planned march to open the exhibition was cancelled by local authorities, fearing that the atmosphere was still too tense. Although life on the streets of Jaramana already seems to be returning to normal, after these events the Druze community lives in fear and uncertainty about its future.

The group, which has been favoured by the Assad regime for decades, now wonders whether their liberal community and culture will survive the political changes. With the change of power in Damascus, many Druze fear that their autonomy will not be respected by the new Sunni government led by President Ahmed Ash-Shara, who, while professing openness and tolerance for every religious group, still does not fully control the radical movements of all the militias that make up his group. Uncertainty about the future makes art more than just a form of manifestation – it becomes a struggle to preserve identity and freedom of expression in a country where secular Druze art can be labelled ‘haram’ – against Islam.